(Regurgitation)

This is a condition in which the aortic valve

has become disfigured to such an extent that its leaflets no

longer are able to completely oppose each other during diastole

(see figures

48a,

48b,

48c,

48d).

This condition allows blood to flow back

into the left ventricle from the ascending aorta during diastole

(figures

48i, 48j,

48k).

Normally, there is no leakage of blood from the ascending aorta

back into the left ventricle after systole.

Aortic valve regurgitation can be caused by

infection of the aortic valve due to syphilis via unprotected

coitus, (figure 205 immediately below) and bacteria, which have

gained access to the blood stream and the aortic valve through

the use of illicit drugs intravenously.

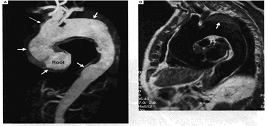

Figure 205

Examination of a 74-year-old man with a one-year

history of mild, stable angina revealed a murmur consistent

with the presence of aortic regurgitation. Echocardiography

demonstrated severe aortic regurgitation as a result of marked

dilatation of the aortic root (diameter, 5.4 cm in the proximal

ascending aorta). Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance

angiography (Panel A) revealed saccular dilatation of the aorta

from its root to beyond the distal arch (short arrows), with

involvement of the innominate artery (long arrow). T1-weighted

images also revealed evidence of mural thrombus in the superior

aspect of the aneurysm, beyond the left subclavian artery (arrow

in Panel B). Serologic immunofluorescence studies revealed the

presence of Treponema pallidum antigen, confirming the clinical

suspicion of syphilitic aortitis and aneurysm. The patient received

10 days of intramuscular penicillin G procaine with oral probenecid

without complications, and he continues to receive medical therapy

under close surveillance.

The cardiovascular complications of syphilis predominantly involve

the aorta, leading to the formation of aneurysms and aortic-valve

incompetence. Angina may result from coronary ostial stenosis

or associated atherosclerosis. The incidence of tertiary syphilis

has declined in recent decades owing to the early recognition

of the disease and the sensitivity of the pathogen to antibiotics.

However, the reemergence of syphilis in the developing world,

particularly among drug abusers and the sexually promiscuous,

may mean that the delayed cardiovascular and neurologic complications

of late syphilis will be seen with increasing frequency.

Pugh,P.J.andGrech,E.D.,N

Engl.Med,Vol.346,No.9,P.676,Feg.28,2002.

These infections may also be caused by bacteria

gaining access to the blood stream from dental procedures.

Certain congenital abnormalities such as bicuspid

aortic valve (see figure

23b) and disorders of connective tissue as well as rheumatic

heart disease (see figure

48b,

111), inflammation of the aorta (Takayasu), high blood pressure,

arteriosclerosis, infective endocarditis (see figure

48c,

48e,

48f), following prosthetic valve surgery including fungus

infection (see above figure 48g), cystic medial necrosis of

aorta are some of the causes of aortic regurgitation.

Myxomatous Aortic Valve Prolapse

The aortic valve has three cusps (right and

left coronary ones and a noncoronary one). In the case of myxomatous

cusps ,there is the finding histologically of a marked increase

in the delicate myxomatous connective tissue between the aortic

surface (thick layer of collagen and elastic tissue forming

the the aortic aspect of the cusp) and the fibrosa or ventricularis,

which is composed of dense layers of collagen and forms the

basic support of the cusp.This myxomatous proliferation of the

acid mucopolysaccharide-containing spongiosa tissue causes focal

interruption of the fibrosa. Secondary effects include fibrosis(scarring)

of the surfaces of the cusps, and ventricular friction lesions.The

valves become redundant and scalloped.

Aortic valve prolapse occurs in 2 % of patients

with mitral valve prolapse(MVP).The primary form of MVP may

occur in families,where it appears to be inherited as an autosomal

dominant trait with varying penetrance. It can also occur in

isolated cases.MVP has been found with incresing frequency in

patients with Marfan syndrome.

MVP is commonly associated with thoracic skeletal

abnormalities such as the straight spine and pectus excavatum.

Some have postulated that MVP results from

fetal exposure to toxic substances during the early part of

pregnancy.

Management of Aortic Insufficiency

All patients with AR need antibiotic prophylaxis

to prevent infective endocarditis. Patients with AR of a rheumatic

origin need antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent recurrences of

rheumatic carditis. Patients with syphilitic AR need a course

of antibiotics to treat syphilis.

Patients with mild AR need no specific therapy (

Table 1 ). They do not need to restrict their activities

and can lead a normal life. Patients with moderate AR also usually

need no specific therapy. These patients, however, should avoid

heavy physical exertion, competitive sports, and isometric exercise.

The value of long-term vasodilators to produce an improvement

in LV size and function has been evaluated in two placebo-controlled

randomized trials. In the hydralazine trial, 36 percent of the

patients were in NYHA functional class II, and patients had

moderate to severe AR. Hydralazine produced modest reduction

of LV end-diastolic volume and a small increase in ejection

fraction at the end of 2 years; however, because of side effects,

long-term compliance was poor, which probably accounted for

the extremely modest beneficial effects. In asymptomatic patients

with severe AR, a calcium channel blocking agent, long-acting

nifedipine, produced significant reductions in blood pressure

and LV end-diastolic volume and mass and major increases in

LV ejection fraction at the end of 1 year. Almost all patients

completed the trial. Recently, a prospective randomized trial

in asymptomatic patients with normal LV systolic function showed

that at the end of 6 years, 34 ± 6 percent of patients

treated with digoxin developed LV systolic dysfunction and/or

symptoms and thus needed valve replacement, compared to 15 ±

3 percent of patients treated with long-acting nifedipine (p

< .001) (

Fig. 48l ); 90 percent (23 of 26) of those who needed valve

replacement had developed LV systolic dysfunction with or without

symptoms; only 3 had become symptomatic without developing LV

systolic dysfunction. Accordingly, all asymptomatic patients

with severe AR and normal LV systolic function should be treated

with a vasodilator (calcium antagonists long-acting nifedipine)

unless there is a contraindication to its use.

The role of nifedipine in patients with moderate AR has not

been studied. In view of its beneficial effects in severe AR,

long-acting nifedipine could be used in selected patients with

moderate AR if there are no contraindications to its use. An

acute study showed that nifedipine was superior to an ACE inhibitor,

and a 6-month trial showed that the results with captopril were

similar to placebo. One study with quinapril involved 10 patients,

many of whom had moderate AR.In another study with enalapril,

most patients had mild to moderate AR and many had severe systemic

hypertension.Moreover, there are no published data to show that

ACE inhibitor therapy reduces the need for valve surgery. In

brief, ACE inhibitors are not of proven benefit in asymptomatic

patients with AR and with normal LV systolic function.

Symptomatic patients with severe AR need medical and surgical

treatment. Medical treatment ( Table 1 below ) consists of the

administration of digitalis, diuretics, and vasodilators. Digitalis

acts by increasing myocardial contractility, often reducing

LV end-diastolic volume while increasing the LV ejection fraction

and also the cardiac output if it is reduced in the resting

state. Digitalis is clearly indicated in patients with symptoms.

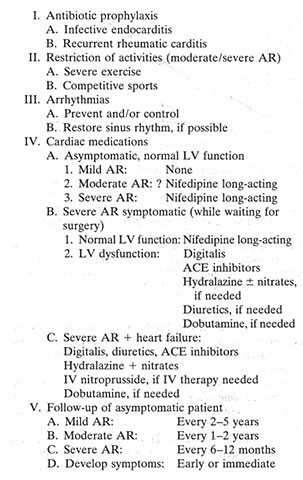

TABLE 1 Medical Treatment of Patients

with Aortic Regurgitation

SOURCE: Copyright © by S. H. Rahimtoola,

M.B., F.R.C.P., M.A.C.P., MA.C.C. See Ref. 93.

The need for and benefits of this therapy

in asymptomatic patients have not been well documented. Diuretics

are of value when the left atrial pressure is elevated and in

the presence of heart failure.

Vasodilators are either arterial, venous, or both. Vasodilators

act by reducing the peripheral arterial resistance, which favors

forward cardiac output and reduces regurgitant volume; initially,

the total LV stroke volume remains unchanged. If the left atrial

pressure is elevated and LV ejection fraction reduced, vasodilators

frequently result in an improvement in both.

Long-term hydralazine therapy in symptomatic patients resuits

in significant benefit in only 20 to 35 percent of patients.Those

who are likely to benefit cannot be predicted. Vasodilators

are indicated in patients who refuse surgery or are not operative

candidates for any reason.

Vasodilators are also indicated for short-term therapy in patients

awaiting valve replacement to optimize their hemodynamics (reduce

filling pressures and increase cardiac output) and thus reduce

their operative risks. If LV systolic function is normal, they

can be given long-acting nifedipine. if they have abnormal LV

systolic function, they should be treated with digitalis and

ACE inhibitors; diuretics and hydralazine, with or without nitrates,

can be used if needed. Small doses of hydralazine (50 mg) are

without therapeutic effect in AR, and larger doses (approximately

100 mg) need to be given only twice daily; the twice-daily regimen

reduces the incidence of side effects. Hydralazine should be

started in small doses and gradually increased, depending on

patient tolerance of the drug.

Vasodilators are of considerable short-term benefit in patients

in functional classes III and IV or heart failure. All such

patients need digitalis, diuretics, and ACE inhibitors. In patients

in functional class IV with heart failure, vasodilators should

ideally be started after the institution of beside henmodynamic

monitoring-that is measuring of pulmonary artery wedge pressure

and cardiac output with the use of ballon flotation catheters.

Hemodynamic monitoring accurately identifies patients who need

the therapy, since clinical judgments can be wrong. It establishes

whether arterial dilators alone will suffice or whether additional

venodilators are needed. Finally, it provides information on

the optimum dosage of vasodilator therapy. After the initial

hemodynamic measurements are made, arterial dilators are given

in progressively increasing dosage until an optimum effect on

cardiac output has been obtained. If cardiac output does not

show any further increase but left atrial pressure is still

very high, additional venodilator therapy should be given. If

the patient is very ill or the hemodynamic abnormalities are

marked, intravenous therapy (e.g., sodium nitroprusside) is

the vasodilator of first choice. In this situation, intravenous

vasodilator therapy should be used only with bedside hemodynamic

monitoring. Inotropic agents, such as dobutamine, may be needed

to improve LV function and increase cardiac output. Low-dose

dopamine may be of value to increase urinary output.

Patients with severe chronic AR need valve

surgery. The correct timing of surgical therapy is now better

defined but is not fully clarified. Valve replacement should

be performed before irreversible LV dysfunction occurs. The

major problem, however, is identifying the precise point at

which LV dysfunction will occur. Here, two major difficulties

are encountered:

(1) patients may already have impaired LV systolic pump function

at rest when they firstpresent or at the time of the first symptom

and

(2) patients with severe symptoms may have normal LV systolic

pump function.

Patients may be in NYHA functional class III (symptoms with

less than ordinary activity), with a normal LV ejection fraction,

or they may be in functional class I (asymptomatic), with a

reduced LV ejection fraction. A reduced LV ejection fraction

demonstrated by two-dimensional echocardiography and/or radionuclide

ventriculography is the best noninvasive indicator of depressed

LV systolic function.

Decisions about surgery in AR should be based on the clinical

functional class and on the LV ejection fraction at rest (

Table 2 ) Patients with chronic severe AR who are symptomatic

(NYHA functional classes II to IV) need valve replacement. Although

there may be some disagreement about recommending valve replacement

to patients with normal ejection fraction who are in functional

class II, we currently would do so. The benefit from valve replacement

has been demonstrated even when the LV ejection fraction is

0.25 or less. As opposed to AS, in which there is no lower level

of ejection fraction that indicates inoperability, it is likely

that some patients with AR and a very low ejection fraction

become inoperable. This level has not been precisely defined

but may be about 0.15 or less. There is a need to individualize

the need for valve replacement in those with very severe LV

systolic dysfunction at rest, in those with very severe LV dilatation

(LV end-diastolic volume index approximately 300 mL/m2),’

and in those with a small regurgitant volume, with a ratio of

regurgitant volume to end-diastolic volume of 0.14 ( Table

2 ). Recent data indicate that patients with severe AR,

LV end-diastolic dimension on echocardiography of approximately

80 mm, and mild to moderate reduction of LV ejection fraction

(mean 0.43) can obtain benefit from valve replacement. Postoperatively,

they are symptomatically improved, LV ejection fraction increases,

and LV size is reduced; the 5-and 10-year survivals are 87 and

71 nercent. respectivelv.

Although.the issue is controversial in some

countries,we believe that patients who are in NYHA functional

class 1 (asymptomatc) and have a reduced ejection fraction at

rest should be offered aortic valve replacement. If the ejection

fraction is normal at rest, one should consider valve replacement

in NYHA functional class I patients if they have severe obstructive

CAD and/or need surgery for other valve disease ( Table

2 ). It is suggested that patients undergo an exercise test

during right heart catheterization if the left ventricle is

large (LV end-diastolic volume approximately 150 mL/m2, LV internal

dimension on M-mode echocardiography of approximately 70 mm

at end diastole and approximately 50 mm at end systole) and/or

the LV ejection fraction shows a new, persistent reduction to

0.54 to 0.60; if the patients have reduced exercise capacity

on treadmill testing; or if ambulatory ECG monitoring demonstrates

ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Valve replacement is recommended

if the pulmonary artery wedge pressure during exercise approximately

20 to 24 mmHg. Patients with associated significant CAD should

have coronary bypass surgery performed at the time of valvular

surgery .

Aortic valve replacement, with or without associated coronary

bypass surgery for obstructive CAD, can be performed at many

surgical centers with an operative mortality of 5 percent or

less. In those without associated CAD or reduced LV systolic

function, the operative mortality may be in the range of 1 to

2 percent. If aortic valve replacement is successful and uncomplicated,

LV volume and hypertrophy regress but do not return to normal;

the beneficial effects on LV size, volume, and mass continue

to be seen up to 5 years after surgery. Impaired LV systolic

pump function improves postoperatively in 50 percent or more

of patients; this improvement is more likely to occur if LV

dysfunction has been present preoperatively for 12 months or

less, and in this subgroup LV ejection fraction usually normalizes.

Even if LV systolic pump function does not improve, there is

a reduction in end-diastolic volume and hypertrophy; from a

cardiac point of view, this is advantageous to the patient.

The 5-year survival of patients undergoing aortic valve replacement

in severe AR is 85 percent (this figure includes operative and

late cardiac deaths). The 5-year survival of patients with LV

ejection fraction _0.45 is 87 percent, versus 54 percent in

patients with an ejection fraction <O.4S.1TM Late survival

after valve replacement for chronic severe AR is best predicted

by variables indicative of LV systolic pump function. Both the

operative mortality and late survival are dependent on cardiac

and LV function and associated noncardiac comorbid factors .

Indeed, in general, the major factors influencing

outcome in patients with valvular heart disease are: LV dysfunction

and its magnitude, duration of LV dysfunction, degree of LV

dilatation, greater NYHA functional class, older age, associated

CAD, and comorbid conditions.

New techniques of aortic valve repair are being developed and

evaluated, and early results are encouraging in selected subgroups.

It is possible that selected patients may eventually need to

have valve repair rather than valve replacement for AR.

The recommendations of the ACC/AHA Practice Guidelines are shown

in Table

3 Guidelines are not and should not be the Law. Application

of such guidelines to clinical practice should be based on the

following principles:

(1) classes I and III applies to all patients in these classes

unless there is a specific clinical circumstance not to do so;

(2) class II applies to patients in this class depending on

the clinical conditions of the patients and the skill and experience

at the individual medical center.

Rahimtoola,S.H.,Aortic Valve Disease,Hurst's

The Heart,10th Edition,Pages 1667-1692