Hypertension is a hemodynamic derangement.

The elevated blood pressure in systemic arterial hypertension

may be associated with an increased cardiac output or vascular

resistance (the hallmark of the disease).

Classification of the various

forms of hypertension based on causes are shown in table

2.

Reference:.Froblich,E.D.MD,Hurst's

The Heart.Pathophysiology of Systemic Arterial Hyper tension,pp1391-1401.

The major hemodynamic alteration in hypertension

is an increased vascular resistance, which is achieved through

an active increase in the state of tone of vascular smooth muscle

in both arterioles and the venules.

This state of vessel tone can be achieved whether

the myocyte is stimulated by enhanced adrenergic input (elevated

circulating levels) of humoral agents (e.g. catecholamines,

angiotensin II, vasopressin, serotonin), local vasoactive peptides

(e.g.angiotensin II, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, endothelium),

or ions (e.g. calcium); by reduced amount of vasoconstrictors;

or by an increase in vasodilating agents (acetylcholine, adenosine,

prostaglandins), local vasoactive peptide (e.g. insulin, calcitonin

gene-related peptide), or ions (e.g. potassium, magnesium, Krebs

intermediate metabolites).

Whatever the myocyte stimulus, there is an increased

availability of calcium ions for the mechanical coupling that

permits the enhanced state of contractility of vascular smooth

muscle. Also, an increased wall to lumen diameter of the arterial

and arteriolar wall, serves to augment vascular responsiveness

to constrictive stimuli and perpetuates the hypertension.

The intravascular (plasma) volume contracts

in patients with essential hypertension and is associated with

a greater degree of interstitial fluid. If a the blood pressure

is lowered by a vasodilator drug, the capillary hydrostatic

and renal arterial perfusion pressure would diminish, causing

the interstitial fluid to migrate intravascularly to expand

the intravascular space and reducing the effectiveness of the

antihypertensive agent. But with the addition of a diuretic,

intravascular volume would again contract, thereby restoring

the anthypertensie effect.

Recently, the angiotensin converting enzyme

and the calcium channel inhibitor therapies have prevented the

expanded intravascular volume and pseudotolerance has been of

less concern.

Reference:.Froblich,E.D.MD,Hurst's

The Heart.Pathophysiology of Systemic Arterial Hyper tension,pp1391-1401.

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated a high

direct correlation between dietary sodium intake of populations

and the prevalence of hypertension. The reduction in sodium

intake to levels below the current recommendation of 100 mmol

per day and the dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet

(DASH) both lower blood pressure substantially with greater

effects in combination than singly.

Reference:Sacks,F.,and

Others:Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and

theDASH diet,N England J Med Vol.344,No.I, Jan.4,2001,pp3-9

;

Reference:.Froblich,E.D.MD,Hurst's The Heart.Pathophysiology

of Systemic Arterial Hyper tension,pp1391-1401.

Complications

of Hypertensive Disease

|

a. Left ventricular hypertrophy.

The left ventricle increases its mass and wall

thickness progressively as a result of the progressive overload

and increased left ventricular wall stress imposed by the increasing

arterial pressure and total peripheral resistance. Ultimately

a stable state is reached and subsequently diastolic dysfunction

occurs, associated with a fourth heart sound, atrial enlargement,

and reduced left ventricular distention.

Ultimately left ventricular systolic function

is impaired and cardiac failure occurs, if arterial pressure

and ventricular afterload are not reduced.

The best means of preventing of preventing morbidity and mortality

is to prevent left ventricular hypertrophy, using early and

continuous antihypertensive therapy.

b.

Myocardial ischemia and infarction.

Both of these complications may occur

due to increased LV pressure and LV chamber diameter leading

to increased oxygen demand in pure LV hypertensive heart disease.

Also, hypertension acclerates the onset of coronary atherosclerosis.

c. Aortic dissection

(to see the entire photographs of figures below click on the

tumbnails: 50, 51b, 51c, 51d, 51e, 51f, 51g, 51h, 51i, 51j,

51k).

Currently, the prevalence of this complication

has diminished due to the use of antihypertensive therapy (especially

beta blocking agents).

A recent study suggest that frequent follow-up

monitoring of patients having aortic intramural hematomas of

the ascending aorta (AIH) in the intensive care unit with CT,

transesophageal echocardiography, and MRI (figures above 51h,

51i, 51j, 51k) along with aggressive medical treatment of their

hypertension can be an option to allow timed surgical repair,

or prevent progression to dissection and rupture and improve

prognosis.

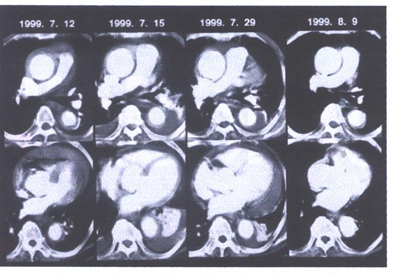

Fig.51i. Serial X-ray computed tomograms (CT)

in a patient with proximal aortic intramural hematoma (case

no. 18). Initial CT (July 12, 1999) showed characteristic crescentic

wall thickening in both the ascending and descending aorta with

a large amount of pericardial effusion. After emergent percutaneous

pericardiocentesis, medical treatment was chosen by the patient,

and CT (July 15, 1999) revealed development of pleural effusion.

The patient's condition stabilized rapidly, although the amount

of pleural effusion increased (July 29, 1999). One month after

the event, complete normalization of the aorta with resorption

of pleural effusion was observed (August 9, 1999).

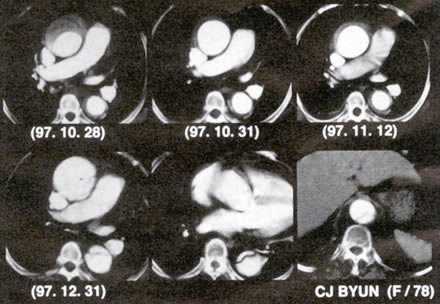

Fig51j. One example of the development of typical

aortic dissection in a patient with proximal aortic intramural

hematnma (case no. 2). Initially, computed tomography showed

dramatic decrease of aortic wall thickening with progressive

enlargement of the lumen of the ascending aorta (October 31

and November 12). About two months after the event, she complained

of chest pain again and follow-up study revealed development

of typical aortic dissection

One predictive factor seems to be the size of

the ascending aorta at the first examination. It has been shown

that patients with an aortic diameter of less than 5cms. had

regression of the hematoma during medical therapy, whereas those

with a larger diameter had a tendency to progression to dissection

or rupture.

Also, the prognosis of very old patients is

acceptable under medical therapy because of severe atherosclerosis

apparently limiting the expansion of hemorrhage under blood

pressure control.

For patients with AIH, emergent surgery has

been the standard practice. But with close monitoring conditions

on an intensive unit, treatment strategies may be individualized.

Symptomatic patients and those with progression during follow-up

and a large ascending aorta should undergo emergent surgery.

But other patients whose condition can be stabilized with antihypertensive

therapy as well as very old patients may be treated medically

with good long-term results.

Reference:Song,J-K,MD,and others,Different

Clinical Features of Aortic Intramural Hematoma Versus Dissection

Involving the Ascending Aorta,JACC,Vol.37,No.6,2001,1603-1610.

Reference:Mohr-Kahaly,MD,Aortic Intramural

Hematoma:From Observation to Therapeutic Strategies,JACC,Vol.37,No.6,2001,1611-1613.

d.

Malignant and accelerated hypertension.

This form of hypertension is less common due to the widespread

use of antihypertension therapy. It represents a sudden accleration

in the vascular disease associated with essential hypertension

and if untreated results in over 97 per cent of involved patients

dying within one year.

It is associated with necrotizing arteriolitis

and severe arteriolar spasm,and reduced blood flow especially

to the kidneys, provoking a state of secondary hyperaldosteronism.

Vigorous antihypertensive treatment will reverse this positive

feedback mechanism.

e.

End stage renal disease and nephrosclerosis.

More frequently, essential hypertension is

associated with renal arteriolar thickening, fibrinoid deposition

in glomeruli, and proteinuria, which follow the development

of left ventricular hypertrophy.

f.

Parenchymal renal disease.

Hypertension is a frequent complication of most renal diseases,

whether glomerulonephritis, polycystic renal disease or others.

This type of hypertension should be considered in any case of

hypertension with anemia of undetermined cause, particularly

if that patient is black.

g. Strokes

Strokes have been dramatically reduced with

antihypertenaive therapy, whether hemorrhagic or thrombic, and

there has been at least a 50% reduction in fatal strokes.

Reference:.Froblich,E.D.MD,Hurst's

The Heart.Pathophysiology of Systemic Arterial Hyper tension,pp1391-1401.

How

Blood Pressure Is Measured

|

Blood Pressure is measured by means of a stethoscope

and an inflatable cuff (figure

122b) that compresses the arm until the brachial artery

is squeezed shut. Intially the artery walls will be closed and

no sounds will be heard through the stethoscope. As air is released

from the cuff a thump will be heard. This is the moment when

the systolic blood pressure-i.e. the first and higher of the

of the two numbers of a person's blood pressure-is recorded.

As the cuff pressure continues to drop below the level of the

systolic pressure, the artery will begin to open and close,

and a rhythmic thumping noise will be audible. When the sound

becomes muffled and faint, the diastolic pressure is recorded.

As the cuff pressure declines below the diastolic pressure in

the artery, the vessel remains open and the sounds disappear

completely (figure

122a).

The cuff size must match the patient's arm,

meaning a big arm requires a bigger cuff, and a smaller one

needs a smaller cuff.

Also, the patient should be sitting or lying

with the arm at the level of the heart while the reading is

obtained.

The patient should be relaxed. Finally caffeine,

nicotine and exercise should be avoided prior to taking the

blood pressure. If the reading is high, it should be repeated

after 2 to 3 minutes of relaxation and rest or later at another

appointment. Also, a 24 hour ambulatory monitor can be done

to check the pressure around the clock (figure

123e).

Reference:Harvard

Men's Health Watch,Feb.2001,pp.1-4

There is no single normal blood pressure; instead

blood pressure readings span a spectrum that ranges from ideal

at the low end to acceptable in the middle and abnormally high

at the top. Interpretations for adults 18 years of age and older

are in figure

123a.

Isolated

systolic hypertension

|

Isolated systolic hypertension with a normal

diastolic reading is the most common form of hypertension in

people 65 and older and its prevalence increases steadidly with

age (figure

123b,

123c). In a recent study of 15,693 people age 60 years old

or above and with systolic blood pressures of 160 or more and

diastolic pressures of 95 or less, without treatment each 10

mmHg rise in systolic blood pressure increased the risk of stroke

by 26%, with strokes accounting for much of the excess mortality.

Drug treatment reduced the risk of stroke by

30%,the risk of heart attacks by 23%, and the risk of death

by 13%.

Reference:Harvard

Men's Health Watch,Feb.2001,pp.1-4

High-Normal Blood Pressure

|

A recent study found that high-normal blood

pressure (systolic pressure of 130 to 139 mm Hg, diastolic pressure

of 85 to 89 mm Hg, or both) is associated with an increased

risk of cardiovascular disease, emphasizing the need to determine

whether lowering such pressures can reduce this risk.

Vasan,R.S. and others,Impact of high

normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease,N

Engl J Med 2001;345:1291-7.,N

Engl

Treatment involves two elements, life style

modification and drug therapy. Diet should be low in sodium

and saturated fat but high in fruits, vegetables, whole grain,

and nonfat dairy products. Exercise, weight and stress control,

and limiting alcohol to no more than two drinks a day are important.

If these measures don't bring blood pressure

down or if there is organ damage or risk factors, then antihypertensive

drug therapy is necessary (figure 123d).

Most authorities suggest a diuretic first (table

6), then adding a beta blocker (table

7) particularly for older patients and those with isolated

systolic hypertension. Patients with diabetes or congestive

heart failure may get better results from angiotensin converting

enyzme (ACE) inhibitors (table

9), and with angina may benefit fron calcium channel blockers

(table

8).

The alpha1-adrenergic blocking agents (table

10) can be used as monotherary or in combination with other

existing progams. They are particularly effective in managing

hypertension associated with pheochromocytoma.

There are also alpha2-adrenoreceptor agonists

(aldomet, which is the preferred drug with hypertension and

ecclampsia; catapres, wytensin, tenex) prescribed as step 2

drugs due to side effects), neuroeffector adrenergic blocking

drugs (hylorel, ismelin, and reserpine, which is the least expensive,

effective, well tolerated) and direct vasodilators (hydralazine).

loniten reserved for multidrug resistant hypertension;

both usually prescribed with a beta-blocker to prevent tachycardia

and a diuretic to prevent edema).

Reference:Harvard

Men's Health Watch,Feb.2001,pp.1-4

Giffford,R.Jr.,Hurst's

The Heart,8th Edition,Treatment of Patients with Systemic Arterial

Hypretension.pp1427-1448

| Diagnostic

Evaluation of the Patient with Systemic Arterial Hypertension

|

Mild

to Moderate Hypertension

|

The clinician should inquire in the patient's

history about the existence of symptoms such as those listed

in table

3 , and perform the evaluation procedures and diagnostic

tests summarized in table

4.

One should look for clues to reversible causes

of the hypertension such as coarctation of the aorta including

diminished leg pulses, delay in the femoral pulse, reduced leg

blood pressure, a coarse systolic murmur at the left sternal

border or rib notching on the chest x-ray (figures

23a,

23b).

Acromegaly, thyroid diseases, Cushing's syndrome

and alcoholism should be suspected from the history and general

appearance of the patient.

In the evaluation a search for target organ damage and cardiovascular

risk factors should be made to include listening for bruits

over the carotid,renal and femoral arteries.

The EKG must be inspected for evidence of ischemia,

and the cholesterol and other tests recommended in table

4 should be performed.

It is important to examine for congestive heart failure by looking

for LVH, rales, ventricular gallop (heart sounds like a gallop),

distended neck veins, edema (swollen feet ankles, legs) amongst

other signs.

Severe,

Accelerated or Malignant Hypertension

|

Diagnostic criteria for malignant hypertension

include a diastolic blood pressure of 125mmHg or more, in conjunction

with target organ damage (retinal hemorrhages, papilla edema,

heart failure, encephalopathy, and renal insufficiency) and

physiologic abnormalities (impaired renal perfusion, elevated

plasma renin andaldosterone levels, increased sympathetic tone).

Renal arteriography may be necessary to diagnose

renal artery stenosis.Also,a plasma catecholamine level is indicated

as well to rule out pheochromcytoma.

Athlete

with Hypertension

|

Marfan's sydrome with aortic regurgitation

and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (figures 39,

39b,

39f)

must be considered.

Echocardiography should be considered in athletes

with abnormal EKG's suggesting LVH with abnormal ST- and T-

wave changes (echocardiographic septal or posterior LV wall

thickness of 13mm or more are uncommon in atheletes with physiologic

LVH).

| DIAGNOSIS

OF TARGET ORGAN DAMAGE |

Advanced retinopathy is associated with a poor

prognosis.

Hypertensive

Cardiovascular Disease

Two major forms of heart disease occur in patients with hypertension:

coronary heart disease (discussed elsewhere on this website)

and hypertensive heart disease. The criteria for hypertensive

heart disease include the presence of hypertension plus LVH

when other causes are excluded.These patients may be susceptible

to myocardial ischemia without evidence of coronary disease.

The EKG is one of the tests used to detect LVH

(table

5).

EKG evidence of left atrial abnormality often

precedes the LV abnormality:

terminal negative atrial forces in V1 above 0.04mm-s, bipeak

interval > 0.04s in deeply notched P waves in any lead,ratio

of P wave duration to PR interval exceeding 1.6 in leadII,and

P wave above 0.3mv height or above 0.12 duration in leadII.

Echocardiographic evidence of LVH (assessing

IVS thickness,LV posterior wall and free wall thickness) occurs

in 30-40% of hypertensive patients whose EKG and chest appear

normal. Thus, the echocardiogram is an early and sensitive indicator

of LVH in patients with hypertension.

Hypertensive

Cerebrovascular Disease

Cerebrovascular

Accidents

|

Hypertension is the most important risk factor

for the development of hemorrhagic or atheroembolic stroke.

Microhemorrhage or occlusion of small vessels can result in

small areas of infarction (lacunar infarcts), which are associated

with neurologic deficits that clear over days to weeks. Multiple

lacunas can lead to to multi-infarct dementia. The differentiation

between a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and a small lacunar

infarct may be difficult but MRI may be able diagnose these

lacunas.

Evanescent neurologic symptoms or findings in

conjunction with a carotid artery bruit justify carotid duplex

Doppler scan and/or angiography in an operable patient.

Hypertensive

Encephalopathy

|

Hypertensive encephalopahy is characterized

by acute to subacute changes in neurologic status that occur

as a result of elevated arterial pressure (especially malignant

hypertension) and are reversed by lowering of the blood pressure

with effective antihypertensive therapy within 12 to 72 hours.

The CT scan and MRI can help diagnose focal areas of intracerebral

hemorrhage or infarction.

Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis

Benign Nephrosclerosis

Malignant Nephrosclerosis

| DIAGNOSIS

OF SECONDARY CAUSES OF HYPERTENSION |

Renovascular

Hypertension Prevalence

|

Renal artery stenosis is the most common curable

of hypertension, but probably occurs in 3% or less of hypertensive

patients. Below the age of 40, renovascular hyprtension is more

frequent in women than men and is less common in the black patients

with hyprtension.

Abdomiminal bruits and severe hypertensive retinopathy

are clues to renovascular disease.

Pathological Types of Renal Artery Stenosis

Fibrous dysplasia and atherosclerosis of the

renal arteries account for almost all cases of renovascular

hypertension.

1. Fibrous Dysplasia

With fibrous dysplasia , hypertension generallly

presents before age 35, most often in women. It is usually unilateral

when initially diagnosed. In 60% of cases there is an upper

abdominal bruit (figure

140 ).

Reference:Safian.R.and

others.RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS,N.Engl.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001.pp431-442

).

2. Atherosclerotic Renovascular Disease

It accounts for two-thirds or more of the patients

with renovascular hypertension, occurring predominantly in men

over 45 years (figure

140 ). At least two-thirds have bilateral lesions (Progressive

atherosclerosis, renal artery stenosis and ischemic nephropathy,

figure

141)

Reference:Safian.R.and

others.RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS,N.Engl.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001.pp431-442

).

Diagnostic Tests are not indicated in patients

with advanced renal failure and bilateral small kidneys.

Reference:Hall,W.D.,AND

OTHERS, Diagnostic Evaluation of the Patient with Systemic Arterial

Hypertension,HURST'S 8TH Edition,The Heart,pp.1403-1425.

(Figure126,

Reference:Safian.R.and others.RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS,N.Engl.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001.pp431-4420

)

Digital subtraction Angiography or Aortography

When the clinical suspicion is high, it is usually

more expedient to proceed directly to arterial DSA or arterigraphy.

Reference:Safian.R.and

others.RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS,N.Engl.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001.pp431-442

).

Reference:Hall,W.D.,AND OTHERS, Diagnostic Evaluation of the

Patient with Systemic Arterial Hypertension,HURST'S 8TH Edition,The

Heart,pp.1403-1425.

Renal vein Renin Ratio (table2a,

Noninvasive Assessment of Renal-Artey Stenosis)

Once the presence of renal arterial disease has been

established, the functional significance of the stenosis can

be evaluated to help determine if the renal artery lesion is

the cause of the hypertension, by measuring the renal vein renin

ratio.A renal vein ratio of 1.5 or greater favoring the stenotic

side is indicative of a functional significant renal artery

lesion.

The renal vein renin ratio is frequently not

reliable for predicting surgical response in patients with bilateral

renovascular disease (figure

142 )

Reference:Safian.R.and

others.RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS,N.Engl.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001.pp431-442

.

Reference:Hall,W.D.,AND OTHERS, Diagnostic Evaluation of the

Patient with Systemic Arterial Hypertension,HURST'S 8TH Edition,The

Heart,pp.1403-1425.

Captopril Renography

Isotope renography detects the acute reductions

of glomerular filtration rate(GFR) following the administration

of captopril to patients with functionally significant renal

artery stenosis and is often an effective screening procedure

for renovascular hypertension. Isotope renography using 99m

Tc-DPTA (reflecting largely glomerular filtration rate) is performed

immediately before and 60 to 90 min. after the administration

of a single 2.5-mg dose of captopril. Following converting enzyme

inhibition,both the uptake and excretion of DPTA on the stenotic

side are usually decreased from baseline in patients with unilateral

renal arterial disease, whereas no consistent decrease is observed

in the contralateral uninvolved kidney (figure 124a).

Reference:Goto,A.

and others,Captopril-Augmented Renal Scan,N.Engi.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001,p430).

This acute reduction in filtration rate that

occurs in the stenotic kidney following converting enzyme inhibition

may be due to interruption of angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction

of the postglomerular efferernt arteriole.

Reference:Hall,W.D.,AND

OTHERS, Diagnostic Evaluation of the Patient with Systemic Arterial

Hypertension,HURST'S 8TH Edition,The Heart,pp.1403-1425.

Atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis is a common

sign of generalized atherosclerosis (figure

142 ) and is frequently associated with hypertension and

excretory dysfunction (figure

141). But the association of renal-artery stenosis with

hypertension or renal insufficiency does not establish causation,

and although the methods for the diagnosis and treatment of

renal insufficiency have improved, the use of invasive diagnostic

techniques and treatment early in the course of the disease

still has no proven benefit.

Further, there seems to be a shift away from

identifying patients with renovascular hyprtension, because

of the known benefits of medical therapy and lack of sustained

cure after percutaneous or surgical revascularization, and a

shift toward identifying patients with renal artery stenosis

who are at risk for excretory dysfunction.

Because of this shift, medical therapy and modification

of risk factors to limit atherosclerosis are essential in all

patients, regardless of whether they have undergone revascularization.

In patients with atherosclerotic renal-artery

stenosis who are at risk for excretory dysfunction, percutaneous

and surgical techniques may improve or stabilize renal function.

The long term results are better in patients who have better

renal function at base line, suggesting that deferring revascularization

until renal function deteriorates may not be the best approach.

Reference:Safian.R.and

others.RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS,N.Engl.J.Med.Vol.344,No.6,Feb.8,2001.pp431-442

Doppler ultrasonography can determine the resistance

to flow in the segmental arteries of both kidneys ( high level

of resistance indicated by resistance-index values of at least

80) , the values for which can be used to predict patients whose

renal function or blood pressure will improve after the correction

of renal -artery stenosis. A renal resistance index value of

at least 80 reliably identifies patients with renal-artery stenosis

in whom angioplasty or surgery will not improve renal function,

blood pressure, or kidney survival.

Reference:Radermacher,J.

and Others, Use of Doppler Ultrasonography

To Predict The Outcome Ofe used to predict patients

whose renal function or blood pressure will improve after the

correction of renal-artery stenosis. A renal resistance index

value of at least 80 reliably identifies patients with renal-artery

stenosis in whom angioplasty or surgery will not improve renal

function, blood pressure, or kidney survival.

Reference:Radermacher,J.

and Others, Use of Doppler Ultrasonography To Predict The Outcome

Of Therapy For Renal-Artery Stenosis,N.Engl. J.Med .2001;344:410-7

TREATMENT

OF PRIMARY PULMONARY

HYPERTENSION - THE NEXT GENERATION

PRIMARY pulmonary hypertension predominantly

affects women, frequently in the prime of life, and usually

leads to death from right ventricular failure within a few years

after diagnosis. It is a vascular disease but is oddly confined

to the small pulmonary arterioles, where intimal fibrosis and

medial hypertrophy lead sequentially to vascular obstruction,

elevated pulmonary vascular resistance, pulmonary hypertension,

and right ventricular overload. Coagulation at the endothelial

surface contributes to obstruction, and thromboembolism may

occur as a secondary event. The right ventricle compensates

through hypertrophy, and although it can sustain function at

high pressures for months to years, decompensation is ultimately

manifested in reduced cardiac output and the development of

peripheral edema. Many conditions and diseases lead to similar

pulmonary vascular lesions and clinical outcomes, including

the scleroderma spectrum of diseases, human immunodeficiency

virus infection, liver disease, and the use of certain anorectic

drugs.These illnesses, along with primary pulmonary hypertension,

are now classified as types of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Primary pulmonary hypertension first came under coordinated

scientific scrutiny when the National Institutes of Health created

the national Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Patient Registry

in 1982, at a time when there was increasing optimism about

a role for vasodilator therapy. Although there had been multiple

previous reports of benefit from beta-agonists, alpha-blockers,

and hydralazine, these responses were usually not sustained,

and the relevant studies were not appropriately powered to detect

true effects. The discovery that calcium-channel blockers could

cause a sustained reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance

in about 20 to 25 percent of previously untreated patients led

to aggressive approaches to short-term vasodilator testing and

long-term vasodilator therapy. Although not every patient with

acute vasodilatation has a durable response to therapy, this

feature carries a favorable prognosis, and many such patients

are treated with calcium-channel blockers alone. It has not

been proved that vasoconstriction is a pathogenetic mechanism

of primary pulmonary hypertension, but this possibility seems

logical and deserves continued study.

What can be done for the 75 percent of patients who do not have

a response to short-term vasodilator therapy? The discovery

that intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) improved functional

capacity, not only in patients with a response to calcium-channel

blockers but also in those without a response, was followed

by evidence that it also improves survival among both types

of patients.This finding has led to widespread use of continuous

intravenous epoprostenol therapy in all patients without a response

to calcium-channel blockers and in most patients with New York

Heart Association class IV heart failure. Beyond the activity

of epoprostenol as a potent vasodilator, its mechanisms of benefit

are unclear, but they may indude a positive inotropic effect,

a small degree of systemic vasodilatation, and antiplatelet

effects, which theoretically could reverse vascular damage.

Epoprostenol therapy by continuous infusion through a central

catheter is expensive - about $60,000 per year - as well as

technically demanding, and it has undesirable side effects.

It is widely recognized that simpler effective therapies are

needed. Prostacyclin analogues given by continuous subcutaneous

infusion, orally, or by intermittent aerosol are under development

as alternatives to the intravenous route. Subcutaneous treprostinil

was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for

further clinical trials. The prostacyclins act through an increase

in the level of the second messenger, intracellular cyclic AMP

(cAMP). Other vasodilators, including inhaled nitric oxide and

oral sildenafil, act by means of cyclic guanosine monophosphate

(cGMP). Sildenafil increases the cGMP level by inhibiting phosphodiesterase

type 5, an enzyme that hydrolyzes cGMP. Clinical studies are

needed to test for potential additive effects of simultaneous

increases in cGMP and cAMP by combining the two classes of drugs.

Safe generation of nitric oxide in vivo might be attained with

the use of oral arginine or citrulline, substrates for the generation

of nitric oxide, with resultant cGMP levels sustained by concomitant

oral sildenafil.

Endothelin-1 is a potent endogenous peptide mediator that has

a role in pulmonary arterial hypertension. It is unclear whether

it has a primary pathogenetic role or whether it is a secondary

mediator that perpetuates disease. Plasma endothelin levels

are increased in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension,

and endothelin is released in increased amounts in the blood

traversing the lung. Endothelin is released by endotheial cells

as big endothelin, which is cleaved to pro-endothelin, which,

in turn, is converted to endothelin-1 (in systemic and lung

vessels) or endothelin-2 (in kidney and gut). Endothelin-1 acts

on two receptors - endothein-A receptors and endothein-B receptors.

Activation of endothelin-B receptors causes the production of

nitric oxide and vasodilatation, and activation of endothelin-A

receptors results in vasoconstriction and smooth-muscle growth.

The ideal endothein-receptor antagonist is likely to be specific

for endothelin-A.

A study using bosentan, a nonspecific endothelin receptor antagonist,

to treat pulmonary hypertension is reported in this issue of

the Journal. Bosentan had small but measurable beneficial effects

in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 213 patients.

The duration of this trial was 16 weeks, which is not sufficient

to test for a difference in mortality, but its results suggest

that endothelin-receptor blockade has a therapeutic role in

some patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. The effect

of bosentan appeared to be limited in most patients, and there

was an unacceptable incidence of abnormal hepatic function at

the higher dose. Because short-term vasodilator testing was

not performed as part of the study, it is not known whether

the patients with the best response to the drug were the same

patients who might have had a response to other vasodilators.

One cannot conclude from this study that bosentan should be

the primary drug for the treatment of primary pulmonary hypertension

or of other causes of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Follow-up

studies are needed to determine the durability of the effect,

whether there are differences in survival, what types of complications

occur, and whether subgroups of patients have different responses

to the drug. It would be useful to measure endothelin levels

and to determine whether there are correlations between these

levels and clinical effects. Studies should be designed to test

whether combining endothelin-receptor antagonists with either

inhibitors of phosphodiesterase type 5 or inducers of cAMP results

in greater functional improvement than does either class of

drug alone.

No current therapies appear to affect the pathogenesis of pulmonary

vascular obstructive disease directly. In rare cases, patients

receiving epoprostenol have had such dramatic responses that

the dose has been reduced, and cessation of drug therapy has

been attempted in a few patients, although the outcomes have

not been published. The recent discovery that the transforming

growth factor beta(TGF-beta) superfamily of receptors is involved

in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension should lead over

the course of the next several years to specific therapies aimed

at the origin of the disease. The evidence suggesting the involvement

of TGF-beta receptors is compelling. About half of studied patients

with familial primary pulmonary hypertension have mutations

in exons of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor II gene

(BMPR2), and the majority of others have genetic linkage to

areas of chromosome 2 near BMPR2, perhaps in a promoter or upstream

regulator or perhaps in intronic DNA. In addition, about 25

percent of patients with sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension

have been found to have mutations in BMPR2. Mutations in the

gene for activin-receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1), another receptor

in the TGF-beta family, are responsible for pulmonary hypertension

in at least some patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.

Clusters of endotheial cells carrying somatic TGF-beta 2-receptor

mutations are found in plexiform lesions in the pulmonary arterioles

of patients with sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension. Studies

of these receptor abnormalities in transfected cells, cell cultures

from patients' tissues, and transgenic mice are under way, and

insights into the relevant mechanisms will certainly emerge

during the next several years. Other promising areas of research

are potassium-channel function and drugs that interrupt the

cycle of growth and repair in diseased pulmonary vessels.

Therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension has progressed from

calcium-channel blockers to prostacydin and now includes adjunctive

therapy with bosentan and, in some patients, sildenafil. Combination

therapies should be tested in the next generation of studies.

It now seems conceivable that the continuous intravenous administration

of epoprostenol through a central catheter will soon be history.

A better understanding of pathogenesis is at hand because the

genes associated with many cases of primary pulmonary hypertension

have been identified, but the development of therapies based

on this knowledge awaits further insights.

JOHN H. NEWMAN, M.D.

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, TN 37232

Newman,J.H.,N Engl Med,Vol.346,No.12,March21,2002

Pp.933-935.